Two days ago the Christian History Institute carried the story of how Dostoevsky’s faith formation affected his writings.

Because I’ve been experiencing quite a bit of physical pain this week, this man’s experience stands out to me. He suffered in many ways, from oppression, great loss, and epilepsy in a time when not much help was available.

I haven’t yet been able to write since my accident, but then, I haven’t even tried. I’m sure, though, that what I’ve been feeling will affect my writing…Dostoevsky’s circumstances certainly did.

I learn so much by reading about authors’ lives, and thought I’d share portions of this for anyone else who might be going through a tough time right now, or who has in the past and can see how that affects your work.

I’d love it if you’d share your thoughts in the comments.

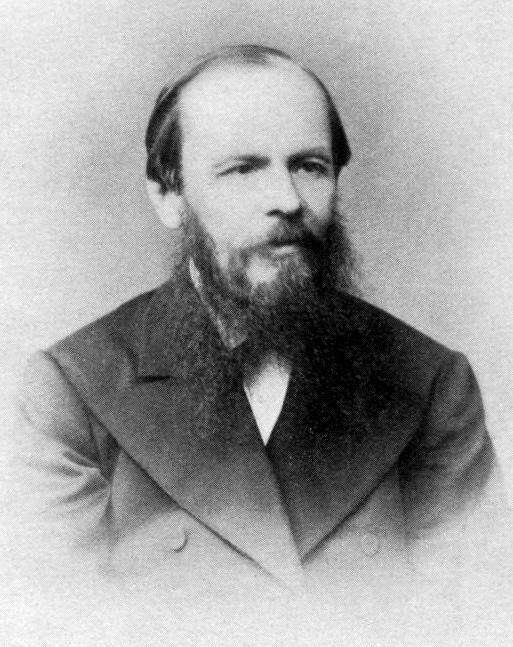

| Saturday, April 23 – Christian History Institute/ author Dan Graves, adapted. MURDER, GUILT, UNJUST IMPRISONMENT, AND FAITH FORMED DOSTOEVSKY’S WRITINGS  [Above: Fyodor Dostoyevsky in 1876—[public domain] Wikipedia] In 1839, when Fyodor Dostoevsky was eighteen, Russian serfs murdered his father, Mikhail. Mikhail, an Orthodox Christian and medical doctor, was a harsh and unsympathetic figure who often vented anger and sarcasm at his children and underlings. Apparently serfs reacted violently to one such outburst. No one ever was prosecuted for the crime. Considering the shock his father’s death gave Dostoevsky, we understand why his writings explore murder and guilt, and true and false religion—and that he aligned himself against serfdom.Dostoevsky completed his first novel, Poor Folk, in 1845. About then he became interested in utopian schemes and networked with socialist intellectuals. In 1847, he joined a group that criticized serfdom and governmental censorship. Denounced to the Ministry of Internal Affairs, Dostoevsky and his friends were arrested on 23 April 1849 as revolutionaries. After spending months in prison, Dostoevsky was sentenced to death. At the last moment, while the prisoners faced a firing squad, a messenger appeared with a reprieve from the czar. The execution turned out to be a cruel hoax, staged for maximum effect. No wonder Dostoevsky’s writings would sometimes detail the last thoughts of dying men. Instead of death, Dostoevsky was condemned to four years in a Siberian penal camp. As he was leaving Saint Petersburg in leg irons, three women handed him a Gospel. He kept this under his pillow in prison and read it over and over, underlining passages that focused on persecution of the just and of coming judgment. Living among Russia’s most depraved convicts and sadistic guards, he lost his illusions about mankind’s inherent goodness. In House of the Dead, he fictionalized some of the horrors he witnessed, and developed the theme of forgiveness. Six years of exile at a military post followed his imprisonment. When he returned to society, his writing showed the deepening impact of years of suffering. In his great novels Crime and Punishment, The Idiot, Demons, and The Brothers Karamazov, protagonists wrestle with conscience and with Christian ideals. Dostoevsky deplores the emptiness of nihilism and exposes the revolutionaries’ slander and double-dealing, laying bare the human condition. In the background of his novels, often indistinct, are Christ and the cross. In Christianity Dostoevsky saw hope for Russian salvation and had no use for atheism, which he believed would devastate the spirit of the peasants. Later in life when he and his wife, Anna, lost their beloved son Alyosha, Dostoevsky sought comfort and counsel from Ambrose of Optina, a famous Russian spiritual advisor. During his many trials, Dostoevsky repeatedly turned to Jesus’s words. He rejoiced that as a child his parents brought him up knowing the Bible stories. As he was dying in 1881, he requested that Anna read his favorite Gospel passages aloud. His epitaph from John 12:24 makes a powerful statement. “Unless a grain of wheat falls to the earth and dies, it remains by itself alone; but if it dies, it bears much fruit.” |

Amen. Praying you’re home and writing your next 12 books soon Ms. Gail.

Ah . . . now that’s FAITH!

Gail, I had no idea you were going through a rough patch. I’ll be sure to keep you in my prayers.

Blessings!

Thanks so much.

Praying for quick healing.

thanks, Candy…maybe not exactly quick, though. (:

Gail, I didn’t realize you’d had an accident and are suffering resultant pain. Prayers upward! God has blessed me beyond words with excellent health and no horrible seasons in life. Upsetting, hurtful, believed to be un-ending, etc., but not to the extent many others have experienced. Dostoevsky is a good example. Thanks for sharing his story.

So many classical authors’ stories/struggles are unknown to us. So much to learn from them! Thanks for your prayers, NEED THEM!

Gail, thank you so much for sharing this. I had no idea you had an accident and were suffering with pain. I’ll certainly pray for you. May the Lord comfort you with His Word and His presence.

Thank you — I so appreciate your prayers.

I’m fine now…and hoping you are healing. Like the other commentors I didn’t know you were going through challenges. Blessings for recovery soon!

The bio of Dostoevsky was very interesting. Praise God he found faith!